The key issue

Design arguments such as the one Hume critiques in "Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion" (1779), compare the complex and ordered nature of the world with complicated and ordered things humans have made (for example machines). The argument is that as things such as machines have been made by someone, this can suggest (by analogy) that a complex and ordered natural world must also be the result of a deliberate act of creation. In other words, where we find complexity in the natural world this is evidence that there is a world maker, who is God.

|

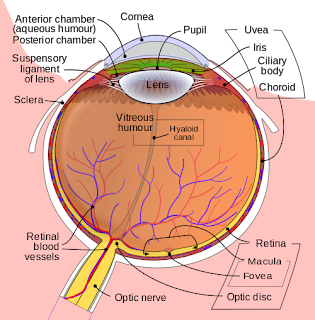

| Schematic diagram of the human eye (Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_eye) |

The success of design arguments is dependent on how close the analogy works to compare the natural world with things humans have made. If the natural world can be shown to be complex and organised without any appeal to outside influences, then the analogy is significantly weakened.

Section 1: The analogy is weak (Chapters 2-4)

The following objections were made in response to an analogy based on building a house:

- Objection 1: The analogy does not compare like-for-like things. We cannot compare the building of a house with the creation of the world. They are too different ("The unlikeness in this case is so striking that the most you can offer on the basis of it is a guess")

- Objection 2: We cannot take one small part of nature and use this "as the model for the whole world" coming into existence ("From observing the growth of a hair, can we learn anything about how men come into being?")

- Objection 3: Why assume the natural realm exhibits evidence of intelligent design, rather than simply the creation of more natural stuff? ("When nature has operated in such a wide variety of ways on this small planet, can we think that she incessantly copies herself throughout the rest of this immense universe?")

- Objection 4: The analogy between building a house and creating a world is only valid if you have seen both a house and a world being built, otherwise the analogy is based on assumptions ("Have worlds ever been formed under your eye")

|

| New house under construction Pittsfield Township Michigan (Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Home_construction) |

- Objection 5: Based on evidence from the (finite) world we live in, we have no reason to conclude that God is infinite ("What right have we (on your theory) to ascribe infinity to God?")

- Objection 6: We have no reason to conclude that God is perfect from looking at the way things are in the world ("Consider the many inexplicable difficulties in the works of nature - illnesses, earthquakes, floods, volcanoes, and so on")

- Objection 7: This world may be one in a line of many "imperfect" worlds made by an "imperfect" God ("It may be that many worlds were botched and bungled, throughout an eternity, before our present system was built")

- Objection 8: Why assume the creation of our world was the work of just one God? ("A great many men join together to build a house")

- Objection 9: The things we see being made around us are created by intelligent humans, why not go the whole way and say that God is also human? ("No man has ever seen reason except in someone of human shape, and that therefore the gods must have that shape")

- Objection 10: God might exist, but why assume God is still around and interested in our world? ("This world was only the first rough attempt of some infant god, who afterwards abandoned it, ashamed of his poor performance")

|

| William Blake's The Ancient of Days (1794) (Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_of_Days) |

Was Hume an atheist or an agnostic?

In the essay "Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion", the character Philo represents Hume's skeptical point-of-view. Before the critiques of the design argument are set out (Chapters 2-5), the character Philo seems to state a version of the Cosmological Argument:

That [God] exists is, as you well observe, unquestionable and self-evident. Nothing exists without a cause; and the original cause of this universe (whatever it may be) we call ‘God’, and piously ascribe to him every kind of perfection.

It should noted that the "First Cause" mentioned here could be God as traditionally believed, or a natural phenomenon such as the 'Big Bang'?

Key quotes

"Since the effects resemble each other, we are led to infer by all the rules of analogy that the causes are also alike, and that the author of nature is somewhat similar to the mind of man."

"The exact similarity of the cases gives us a perfect assurance of a similar outcome... But the evidence is less strong when the cases are less than perfectly alike; any reduction in similarity, however tiny, brings a corresponding reduction in the strength of the evidence; and as we move down that scale we may eventually reach a very weak analogy."

Key Text